Find closest pair of point with Plane Sweep Algorithm in O(n ln n)

Finding the closest pair of Point in a given collection of points is a standard problem in computational geometry. In this article I'll explain an efficient algorithm using plane sweep, compare it to the naive implementation and discuss its complexity.

This problem is standard, but not really easy to solve in an efficient way. The first implementation we think of is the naive one, comparing each point to each other point.

In my examples, I'll use the java.awt.Point class to represent a point. This naive implementation is really easy to implement :

public static Point[] naiveClosestPair(Point[] points) { double min = Double.MAX_VALUE; Point[] closestPair = new Point[2]; for (Point p1 : points) { for (Point p2 : points) { if (p1 != p2) { double dist = p1.distance(p2); if (dist < min) { min = dist; closestPair[0] = p1; closestPair[1] = p2; } } } } return closestPair; }

As you can directly see, this naive implementation has a complexity of O(n^2). But we can do a lot better using a plane sweep algorithm.

With that algorithm, we'll sweep the plane from left to right (right to left is also a possibility) and when we reach a point we'll compute all the interesting candidates (the candidates that can be in the closest pair).

For that we'll make the following operations :

- We sort the list of points from left to right in the x axis

- And then for each point :

- We remove from the candidates all the point that are further in x axis that the current min distance

- We take all the candidates that are located more or less current min distance from the current point in y axis

- We test for the min distance all the founded candidates with the current point

- And finally we add the current point to the list of candidates

So when we found a new min distance, we can make the rectangle of candidates smaller in the x axis and smaller in the y axis. So we made a lot less comparisons between the points.

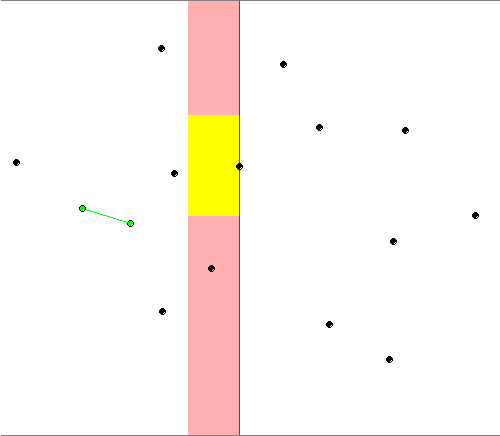

Here is a picture illustrating that :

The red points are the closest pair at this time of the algorithm. The red rectangle is the rectangle of the candidates delimited in right by the current point. And the yellow rectangle contains only the candidates interesting for the current point.

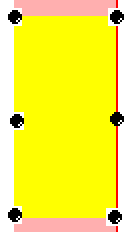

There is always a maximum of 6 points in the yellow rectangle, the 4 vertices, the point with the same coordinates as the current point and finally the point in the same y coordinate and in the limit of the x axis. Even if the maximum is 6, you'll almost never have more than 2 points in that list (the maximum is see in my test was 3 with a collection of 1'000'000 random points). You can see this 6 points here :

If all that stuff is not really clear for you, you can watch it in action here in a Java applet.

The candidates must also be always sorted. For that, we'll use a Binary Search Tree for good performances.

If we look at the complexity :

- Sorting all the points in right axis : Cost O(n ln n) with Quick Sort by example

- Shrinking the list of candidates take O(n) from start to end of the algorithm because we add n points to the candidates and we can remove only n points. So this is constant for each point : O(1).

- Searching all the candidates between two values in y axis cost O(ln n) with binary search

- The comparisons with at maximum 6 points are made in O(1)

- Add the candidates and keep the list of candidates sorted cost O(ln n).

So the total complexity is O(n ln(n) + n * ( 1 + ln(n) + 1 + ln(n) ) ) = O(n ln n).

So it's really better than O(n^2) for the naive implementation.

So now, we can go to the implementation in Java.

public static Point[] closestPair(Point[] points) { Point[] closestPair = new Point[2]; //When we start the min distance is the infinity double crtMinDist = Double.POSITIVE_INFINITY; //Get the points and sort them Point[] sorted = Arrays.copyOf(points, points.length); Arrays.sort(sorted, HORIZONTAL_COMPARATOR); //When we start the left most candidate is the first one int leftMostCandidateIndex = 0; //Vertically sorted set of candidates SortedSet<Point> candidates = new TreeSet<Point>(VERTICAL_COMPARATOR); //For each point from left to right for (Point current : sorted) { //Shrink the candidates while (current.x - sorted[leftMostCandidateIndex].x &gt; crtMinDist) { candidates.remove(sorted[leftMostCandidateIndex]); leftMostCandidateIndex++; } //Compute the y head and the y tail of the candidates set Point head = new Point(current.x, (int) (current.y - crtMinDist)); Point tail = new Point(current.x, (int) (current.y + crtMinDist)); //We take only the interesting candidates in the y axis for (Point point : candidates.subSet(head, tail)) { double distance = current.distance(point); //Simple min computation if (distance < crtMinDist) { crtMinDist = distance; closestPair[0] = current; closestPair[1] = point; } } //The current point is now a candidate candidates.add(current); } return closestPair; }

The code isn't overcomplicated. We see all the steps explained in the article and that works well. The Horizontal and Vertical comparators are really simple :

private static final Comparator<Point> VERTICAL_COMPARATOR = new Comparator<Point>() { @Override public int compare(Point a, Point b) { if (a.y < b.y) { return -1; } if (a.y > b.y) { return 1; } if (a.x < b.x) { return -1; } if (a.x > b.x) { return 1; } return 0; } }; private static final Comparator<Point> HORIZONTAL_COMPARATOR = new Comparator<Point>() { @Override public int compare(Point a, Point b) { if (a.x < b.x) { return -1; } if (a.x > b.x) { return 1; } if (a.y < b.y) { return -1; } if (a.y > b.y) { return 1; } return 0; } }

Here is a performance comparison for some sizes with a Benchmark Framework I described here for some sizes of collection points.

| Naive | Sweeping | |

| 100 | 189.923 us | 53.685 us |

| 500 | 4.448 ms | 279.042 us |

| 1000 | 17.790 ms | 556.731 us |

| 5000 | 458.728 ms | 3.320 ms |

Like you can see, this is really better than the naive implementation. So we make a good job. But if we make one more test with 10 elements :

| Naive | Sweeping | |

| 10 | 1.932 us | 4.746 us |

Now our good sweeping algorithm is slower than the naive !

When we think about that, we realize that it's logical. In fact we made a lot of computations before starting the algorithm like sorting the points, creating a list of candidantes, ... All that stuff is heavier than make n^2 comparisons in little number. So what can we do to have good performances with small number of points ?

It's really easy to solve. We just have to found the number before which the naive algorithm is quicker than the sweeping and when the size of the points collection is smaller than this pivot number we use the naive implementation. On my computer I found that before 75 elements, the naive implementation was faster than the sweeping algorithm, so we can refactor our method :

public static Point[] closestPair(Point[] points) { if(points.length < 75){ return naiveClosestPair(points); } //No changes }

And we've good performances for little set of points :)

So our method is now complete. I hope you found that post interesting and that will be useful to someone.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus